Washington Post Opinion: Struck from a jury for being Black? It still happens all too often.

By Stephen Bright | February 14, 2024 at 7:30 a.m. EST

Stephen Bright, a former director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, teaches at Yale Law School and the Georgetown University Law Center and is the author, with James Kwak, of “The Fear of Too Much Justice: Race, Poverty, and the Persistence of Inequality in the Criminal Courts.”

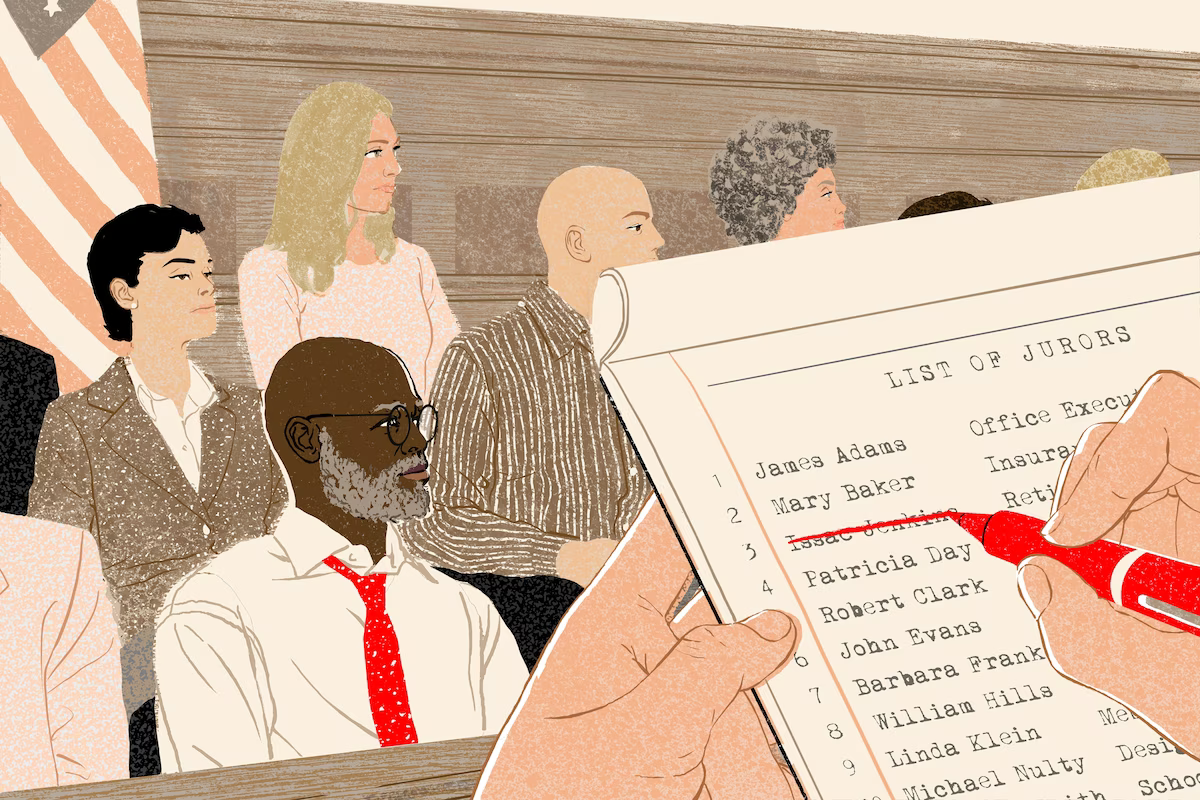

The Supreme Court has long held that the Constitution prohibits prosecutors from striking Black people from jury service based on their race. Yet the practice continues: Nearly every study of jury strikes has revealed that prosecutors disproportionately use their strikes to exclude Black jurors.

Now the court has an opportunity to send a message to prosecutors across the country that this abhorrent practice is unacceptable — and it should not hesitate to do so.

The right to a fair trial before an impartial jury of one’s peers is one of the criminal legal system’s most basic principles. But for many Black people, the promise is illusory.

Black citizens are often completely or substantially underrepresented on juries, especially in death penalty cases. Some are dismissed because they express reservations about capital punishment — often because of its long history of discrimination against Black people. Then prosecutors use their peremptory strikes, which allow each side to remove a set number of prospective jurors for any reason, against those who remain. As a result, all-White juries are still common in criminal trials, even in communities with substantial minority populations.

The Supreme Court prohibited strikes based on race in its 1986 decision in Batson v. Kentucky. The court held that if there is a pattern of strikes that appears to be based on race, prosecutors must show the strikes were for other, race-neutral reasons. The court has reaffirmed this in several decisions since then, including a Mississippi case in which the defendant faced the death penalty and a prosecutor had the opportunity to strike 42 Black citizens in six trials of the same case — and struck 41 of them.

And yet prosecutors routinely get away with striking based on race because courts fail to scrutinize their often-flimsy excuses, which include such dubious reasons as alleged low intelligence, lack of eye contact with prosecutor, living in a high-crime neighborhood or showing boredom or inattentiveness. A Texas judge observed that courts were so willing to accept “any implausible or outlandish reason” for a strike that it rendered the Supreme Court’s decision in Batson “meaningless.”

That could change now, if the Supreme Court agrees to review the case of Warren King, a Black man on Georgia’s death row.

King, who is intellectually limited and diagnosed with schizophrenia, was just 18 years old, with no history of violence, when his cousin Walter Smith recruited him to rob a convenience store in 1994. Smith supplied the gun and getaway car. During the robbery, the White store clerk, Karen Crosby, was shot and killed. Smith claimed King was the shooter; King said it was Smith.

Prosecutors cut a deal with Smith, who testified against King and was sentenced to life imprisonment with the possibility of parole. King was convicted and sentenced to death.

The prosecutor at King’s trial, John Johnson, struck seven of eight prospective Black jurors (87 percent) and only three of 34 White ones (8 percent). Put another way, Johnson was 10 times more likely to strike a Black juror than a White one in King’s case.

King’s lawyers objected based on Batson, requiring Johnson to provide “race-neutral” reasons for his strikes. Johnson, whose 40-year career was reportedly marked by “persistent allegations of misconduct,” countered by expressing his hostility to the Batson decision and to the court’s deciding whether he had discriminated.

When Johnson eventually offered reasons for his strikes, the judge ruled that he had violated Batson in striking one Black woman, finding that the reasons he gave were pretexts for discrimination. Johnson launched into a long rant, saying he could be “screwed” if the woman sat on the jury. He expressed such anger that the judge told him to calm down and pull himself together before saying anything more.

But the judge did not find discrimination with regard to the other six strikes of Black jurors. In upholding King’s conviction, two judges of a federal court of appeals called the strikes “troubling” but allowed them. The third judge dissented, arguing that Johnson’s “open disdain and outright contempt for Batson” and the abundant evidence of discrimination showed a violation of that ruling.

That judge pointed out that Johnson struck all three Black jurors who knew King and his family, but none of the four White jurors who did. Johnson also said he struck a Black woman because her husband, another prospective juror in the case, had said she was opposed to the death penalty. But the transcript showed that the husband testified he did not know her position on capital punishment and that his wife had said she could consider it.

This was egregious racial discrimination.

Because King did not receive a fair trial by an impartial jury and now faces the ultimate punishment, the Supreme Court should take his case and make clear once again that such discrimination has no place in the legal system.

Editor’s Note: This Washington Post article reinforces the concerns, arguments and challenges MRT’s legal (trial and appellate) teams have raised since the jury, in his case, was selected in March of last year. Further, it is a critical section the Appellate Opening Brief and the subject of an entire Amicus Brief submitted by several legal scholars across the United States.